This article is currently a draft

Note: you don’t need to know Japanese to read this part

Contents

A word of warning: this series is an excessively-detailed, low-level view of how Japanese works that the vast majority of people don’t need to know. If you ask an advance Japanese learner what they know about Japanese dependency grammar, they probably have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s not detrimental to your learning, but I have no prior research to support that knowing about these concepts will accelerate your Japanese learning.

It might also help to read this in chunks and take breaks to digest the information. Making up your own example sentences so you can get a better grasp of the concepts also helps.

Linguistic Primer

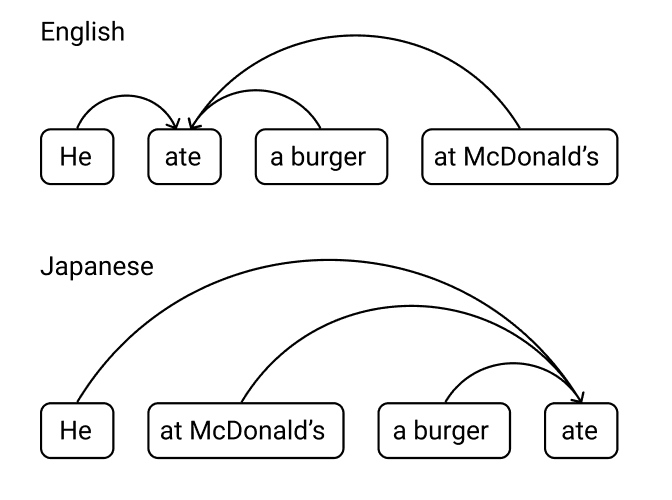

Before we begin, let’s dive into what makes English and Japanese different. You might have heard that English is a subject-verb-object (SVO) language while Japanese is a subject-object-verb (SOV) language. We can show this using a simple example like “he ate a burger”. Using Japanese grammar structure, it would be “he burger ate”.

We can see a pattern start to emerge as we expand this example. “He ate a burger at McDonald’s”. In Japanese, the sentence would be structured as “he at McDonald’s burger ate”. Who’s doing the eating? He is. What was eaten? The burger. Where? McDonald’s. The same information is conveyed, but in the English sentence, additional descriptors/modifiers are inserted after the verb while in Japanese, it’s inserted in between the subject and the verb. We can think of these modifiers as being answers to question words (who, what, where, when, etc.).

We can generalize this pattern using a tree analogy. The branches are the descriptors/modifiers, and the root (in linguistics the official name is head) is what they all describe. We can visualize this by calling upon a field of linguistics called dependency grammar and drawing what is called sentence diagrams. A sentence is separated into chunks of information, and you draw arrows from the information to what it’s informing about. As you read each chunk, an arrow appears as a loose end that then gets tied down to another chunk somewhere else in the sentence. These arrows represent answers to question words.

As you can see, the diagram looks completely different in English than in Japanese. In the English diagram, the arrows are shorter which represents a shorter term “storage” of information before they are distributed. Also note that in this English sentence, you are only storing one block of information at a time, while in the Japanese version, you have to store three blocks of information before finding their main dependency. This is because in English, you get the root of the sentence fairly early on and the rest of the sentence is just additional details that you can easily connect, while in Japanese, the root is at the end of the sentence and you’re collecting all the details before you reach it. You’re storing more unconnected blocks of information for a longer amount of time in Japanese.

Because of this, English is considered a predominantly right-branching, head-initial language, while Japanese is considered an almost exclusively left-branching, head-final language.

Why Native English Speakers Have a Hard Time

The reason why native English speakers have a hard time deciphering Japanese sentences is because they are used to picking up each word in a sentence and immediately linking it to its dependency. They want to be able to answer the question words as soon as possible. But Japanese doesn’t work like that. Because of the left-branching nature of Japanese, a Japanese sentence is understood by collecting the details first and then distributing it when needed. Japanese is always modified on the left. i.e. you get the description of the item before the item itself.

This is why some Japanese learning material say to read sentences backwards to understand it better. When you read a Japanese sentence backwards, you’re more in-line with the dependency structure of English. But this is a terrible idea. If you build a habit of working backwards, imagine what happens when someone tries to speak to you. You can only begin to understand the sentence once they finish speaking it, but by that point they’re already moved on to speaking the next sentence!

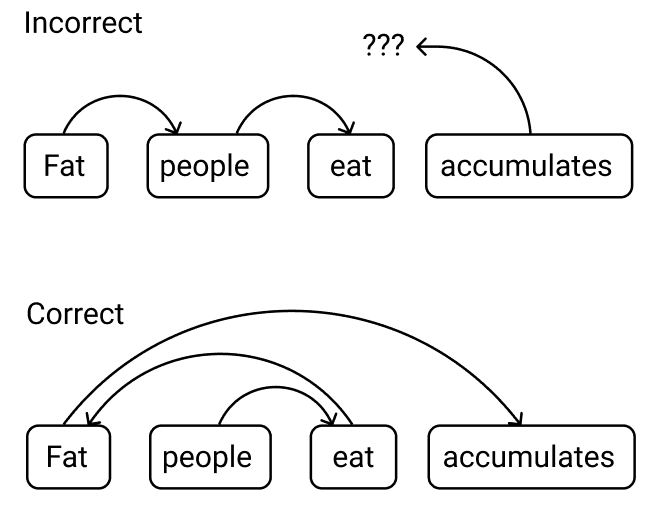

You can experience a similar dependency disconnect in English by reading sentences that are structured to require more long-distance detail attribution to understand correctly. For example, the sentence: “Fat people eat accumulates”. You probably had to read that sentence twice. Let’s use question words to identify where the confusion happened.

- We start at the word “fat”. As the only word encountered so far, this is a loose end.

- We encounter the word “people”. We can now answer a question word. What kind of people? “Fat” people. We link the word “fat” with the word “people”. The phrase “fat people” is now a loose end.

- We get to the word “eat”. We can answer another question word. Who eats? We only have one loose end, so “fat people” eat. We assume that the verb “eat” is the root of the sentence. “Fat people eat” is now a loose end.

- We hit the end of the sentence with the word “accumulates”. Now what? We can’t answer any of our question words with the loose ends we have. Saying that “fat people eat” accumulates isn’t correct. Something went wrong.

If you want to reach the correct understanding, here are the correct questions to ask: Who eats? People eat. What kind of fat? Fat people eat. What accumulates? Fat people eat accumulates.

I can’t say that there’s no syntactic ambiguity in Japanese, but in normal conversations, things like this rarely happen. If we didn’t have to make intermittent assumptions about the role of the words in a sentence, we wouldn’t have incorrectly group words together and got confused by this sentence. This is where two features of Japanese combine to really make sentence diagrams useful. In the next part, we zoom in and take a look at the dependency rules and structure of Japanese.

Resources Used